Δευτέρα 30 Μαρτίου 2009

Πέμπτη 26 Μαρτίου 2009

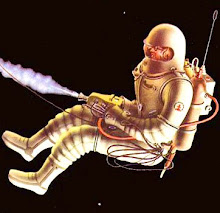

man with a movie camera

The film has an unabashedly art film style, and emphasizes that film can go anywhere. For instance, the film uses such scenes as superimposing a shot of a cameraman setting up his camera atop a second, mountainous camera, superimposing a cameraman inside a beer glass, filming a woman getting out of bed and getting dressed, even filming a woman giving birth, and the baby being taken away to be bathed.

Vertov's message about the prevalence and unobtrusiveness of filming was not yet true—cameras might have been able to go anywhere, but not without being noticed; they were too large to be hidden easily, and too noisy to remain hidden anyway. To get footage using a hidden camera, Vertov and his brother Mikhail Kaufman had to distract the subject with something else even louder than the camera filming them.

The film also features a few obvious stagings such as the scene of the woman getting out of bed and getting dressed (cameras at the time were fairly bulky and loud, and not surreptitious) and the shot of the chess pieces being swept to the center of the board (a shot which was spliced in backwards, causing the pieces to expand outward and stand into position). The film was criticized for both the stagings and its stark experimentation, possibly as a result of its director's frequent assailing of fiction film as a new "opiate of the masses."

music by cinematic orchestra (Σάββατο 28 Μαρτίου στο Fuzz club)

ακολουθούν 3 πρώτα μέρη.. υπόλοιπο youtube..enjoy

Τετάρτη 18 Μαρτίου 2009

Xploding Plastix

Xploding Plastix is the musical child of Jens Petter Nilsen and Hallvard Hagen. Both based in Oslo, they started making music together sometime in late ‘98 or early ‘99. After about a year of playing, sampling, programming and focused tune writing; they decided it was time to let the public hear what they’d been up to. This resulted in a 6 track demo in late ‘99. About 22 hours after first shipment, record companies were on the phone, and 4 months later, 5 out of 6 tracks had been released on various labels.

The duos debut album Amateur Girlfriends Go Proskirt Agents was released in 2001 via Norwegian label Beatservice. Subsequently they moved over to Sony and recorded The Doncamatic Singalongs, which was never released outside Scandinavia, despite the announcement of an international release date.

With their momentum taken from underneath them by Sony, Xploding Plastix never acheived their full potential. Though no split has been announced, their website has not been updated since February 2006, when it was announced that the Kronos Quartet sould perform their perform their three movement composition, The Order of Things: Music for the Kronos Quartet.

Xploding Plastix has a very organic sound; throwing saccharine analogue melodies to foreground the acoustic quality; imposing a distinctive live feel. A certain raw edge. An oeuvre of an ear-opener: Zipping and unzipping the beat, a beat-science out-of the ordinary. Emphasizing the flowing warmth and organity of the rhythms. Triggering flailing, skittering, skipping and spinning breaks, makes this pure nigthvision!

Παρασκευή 13 Μαρτίου 2009

Vincent

The Raven

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore,

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

"'Tis some visitor," I muttered, "tapping at my chamber door-

Only this, and nothing more."

Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December,

And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.

Eagerly I wished the morrow;- vainly I had sought to borrow

From my books surcease of sorrow- sorrow for the lost Lenore-

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore-

Nameless here for evermore.

And the silken sad uncertain rustling of each purple curtain

Thrilled me- filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before;

So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating,

"'Tis some visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door-

Some late visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door;-

This it is, and nothing more."

Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer,

"Sir," said I, "or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore;

But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping,

And so faintly you came tapping, tapping at my chamber door,

That I scarce was sure I heard you"- here I opened wide the door;-

Darkness there, and nothing more.

Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering,

fearing,

Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortals ever dared to dream before;

But the silence was unbroken, and the stillness gave no token,

And the only word there spoken was the whispered word, "Lenore!"

This I whispered, and an echo murmured back the word, "Lenore!"-

Merely this, and nothing more.

Back into the chamber turning, all my soul within me burning,

Soon again I heard a tapping somewhat louder than before.

"Surely," said I, "surely that is something at my window lattice:

Let me see, then, what thereat is, and this mystery explore-

Let my heart be still a moment and this mystery explore;-

'Tis the wind and nothing more."

Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and

flutter,

In there stepped a stately raven of the saintly days of yore;

Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed

he;

But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door-

Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door-

Perched, and sat, and nothing more.

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore.

"Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou," I said, "art sure no

craven,

Ghastly grim and ancient raven wandering from the Nightly shore-

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night's Plutonian shore!"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."

Much I marvelled this ungainly fowl to hear discourse so plainly,

Though its answer little meaning- little relevancy bore;

For we cannot help agreeing that no living human being

Ever yet was blest with seeing bird above his chamber door-

Bird or beast upon the sculptured bust above his chamber door,

With such name as "Nevermore."

But the raven, sitting lonely on the placid bust, spoke only

That one word, as if his soul in that one word he did outpour.

Nothing further then he uttered- not a feather then he fluttered-

Till I scarcely more than muttered, "other friends have flown

before-

On the morrow he will leave me, as my hopes have flown before."

Then the bird said, "Nevermore."

Startled at the stillness broken by reply so aptly spoken,

"Doubtless," said I, "what it utters is its only stock and store,

Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful Disaster

Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore-

Till the dirges of his Hope that melancholy burden bore

Of 'Never- nevermore'."

But the Raven still beguiling all my fancy into smiling,

Straight I wheeled a cushioned seat in front of bird, and bust and

door;

Then upon the velvet sinking, I betook myself to linking

Fancy unto fancy, thinking what this ominous bird of yore-

What this grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt and ominous bird of yore

Meant in croaking "Nevermore."

This I sat engaged in guessing, but no syllable expressing

To the fowl whose fiery eyes now burned into my bosom's core;

This and more I sat divining, with my head at ease reclining

On the cushion's velvet lining that the lamplight gloated o'er,

But whose velvet violet lining with the lamplight gloating o'er,

She shall press, ah, nevermore!

Then methought the air grew denser, perfumed from an unseen censer

Swung by Seraphim whose footfalls tinkled on the tufted floor.

"Wretch," I cried, "thy God hath lent thee- by these angels he

hath sent thee

Respite- respite and nepenthe, from thy memories of Lenore!

Quaff, oh quaff this kind nepenthe and forget this lost Lenore!"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."

"Prophet!" said I, "thing of evil!- prophet still, if bird or

devil!-

Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore,

Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted-

On this home by horror haunted- tell me truly, I implore-

Is there- is there balm in Gilead?- tell me- tell me, I implore!"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."

"Prophet!" said I, "thing of evil- prophet still, if bird or

devil!

By that Heaven that bends above us- by that God we both adore-

Tell this soul with sorrow laden if, within the distant Aidenn,

It shall clasp a sainted maiden whom the angels name Lenore-

Clasp a rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore."

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."

"Be that word our sign in parting, bird or fiend," I shrieked,

upstarting-

"Get thee back into the tempest and the Night's Plutonian shore!

Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken!

Leave my loneliness unbroken!- quit the bust above my door!

Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my

door!"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."

And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon's that is dreaming,

And the lamplight o'er him streaming throws his shadow on the

floor;

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted- nevermore!

Τρίτη 10 Μαρτίου 2009

Ten Days That Shook the World

Director: Grigori Aleksandrov and Sergei M. Eisenstein.

Music: Dimitri Shostakovich

Eisenstein's montage theories are based on the idea that montage originates in the "collision" between different shots in an illustration of the idea of thesis and antithesis. This basis allowed him to argue that montage is inherently dialectical, thus it should be considered a demonstration of Marxism and Hegelian philosophy. His collisions of shots were based on conflicts of scale, volume, rhythm, motion

ακολουθούν τα 3 πρώτα μέρη... το υπόλοιπο youtube..enjoy

Πέμπτη 5 Μαρτίου 2009

Τρίτη 3 Μαρτίου 2009

Plato's Cave

Μετά από αυτά όμως, είπα, φαντάσου την ανθρώπινη φύση ως προς την παιδεία και την απαιδευσία, σαν μια εικόνα που παριστάνει μια τέτοια κατάσταση. Δες λοιπόν με τη φαντασία σου ανθρώπους που κατοικούν μέσα σε μια σπηλιά κάτω από τη γη, που να έχει την είσοδό της ψηλά στην οροφή, προς το φως, σε όλο το μήκος της σπηλιάς μέσα της να είναι άνθρωποι αλυσοδεμένοι από την παιδική ηλικία στα πόδια και στον αυχένα, έτσι ώστε να είναι καρφωμένοι στο ίδιο σημείο και να μπορούν να βλέπουν μόνο μπροστά τους και να μην είναι σε θέση, εξαιτίας των δεσμών, να στρέφουν τα κεφάλια τους ολόγυρα. Κι οι ανταύγειες της φωτιάς που καίει πίσω τους να είναι πάνω και μακριά από αυτούς. Και ανάμεσα στη φωτιά και στους δεσμώτες, προς τα πάνω, να υπάρχει ένας δρόμος που στο πλάι του να είναι χτισμένο ένα τοιχάκι, όπως τα παραπετάσματα που τοποθετούν οι θαυματοποιοί μπροστά από τους ανθρώπους, και πάνω απ' αυτά τους επιδεικνύουν τα ταχυδακτυλουργικά τους.

Βλέπω, είπε.

Φαντάσου λοιπόν κοντά σε τούτο το τοιχάκι, ανθρώπους να μεταφέρουν αντικείμενα κάθε είδους, που προεξέχουν από το τοιχάκι, καθώς και ανδριάντες και κάποια άλλα αγάλματα ζώων, πέτρινα και ξύλινα και κατασκευασμένα με κάθε είδους υλικό, και, όπως είναι φυσικό, από αυτούς που τα μεταφέρουν άλλοι μιλούν και άλλοι μένουν σιωπηλοί.

Παράδοξη εικόνα περιγράφεις, και παράδοξους συνάμα δεσμώτες, είπε.

Μα είναι όμοιοι με μας, είπα εγώ και πρώτα και κύρια, νομίζεις πως αυτοί έχουν δει κάτι άλλο από τους εαυτούς τους και τους υπόλοιπους που είναι μαζί, εκτός από τις σκιές που δημιουργεί η φωτιά, και που αντανακλούν ακριβώς απέναντί τους στον τοίχο της σπηλιάς;

Μα πως είναι δυνατόν, είπε, αφού είναι αναγκασμένοι να κρατάνε ακίνητα τα κεφάλια τους εφ' όρου ζωής;

Κι από αυτά που μεταφέρονται ; Δεν θα έχουν δει ακριβώς το ίδιο;

Τι άλλο;

Κι αν θα μπορούσαν να συνομιλούν μεταξύ τους, δεν νομίζεις πως σ' αυτά που βλέπουν θεωρούν πως αναφέρονται οι ονομασίες που δίνουν;

Αναγκαστικά.

Τι θα συνέβαινε, αν το δεσμωτήριο τους έστελνε αντίλαλο από τον απέναντι τοίχο, κάθε φορά που κάποιος από τους περαστικούς μιλούσε, νομίζεις πως θα θεωρούσαν πως αυτός που μιλάει είναι τίποτε άλλο από τη φευγαλέα σκιά;

Μα το Δία, όχι βέβαια, είπε.

Και σε κάθε περίπτωση, είπα εγώ, αυτοί δεν θα θεωρούν τίποτα άλλο σαν αληθινό, παρά τις σκιές των αντικειμένων.

Απόλυτη ανάγκη, είπε.

Σκέψου όμως, είπα εγώ, ποια θα μπορούσε να είναι η λύτρωσή τους και η θεραπεία τους και από τα δεσμά κι από την αφροσύνη, αν τους συνέβαιναν τα εξής: Αν κάθε φορά, δηλαδή, που θα λυνόταν κάποιος και θ' αναγκαζόταν ξαφνικά να σταθεί και να βαδίσει και να γυρίσει τον αυχένα του και να δει προς το φως, κι όλ' αυτά θα τα έκανε με μεγάλους πόνους και μέσα από τα λαμπυρίσματα δεν θα μπορούσε να διακρίνει εκείνα, που μέχρι τότε έβλεπε τις σκιές τους, τι νομίζεις πως θ' απαντούσε αυτός, αν κάποιος του έλεγε πως τότε έβλεπε φλυαρίες, ενώ τώρα είναι κάπως πιο κοντά στο ον και πως έχει στραφεί προς όντα που πραγματικά και βλέπει με σωστότερο τρόπο, και αν του έδειχνε το καθένα από αυτά που περνούσαν, ρωτώντας τον τι είναι και αναγκάζοντάς τον ν' αποκριθεί, δεν νομίζεις πως αυτός θ' απορούσε και θα νόμιζε πως αυτά που έβλεπε τότε ήταν πιο αληθινά από τα τωρινά που του δείχνουν;

Και πολύ μάλιστα, είπε.

Κι αν λοιπόν τον ανάγκαζε να βλέπει προς το ίδιο το φως, δεν θα πονούσαν τα μάτια του και δεν θα έφευγε για να ξαναγυρίσει σ' εκείνα που μπορεί να δει καλά, και δεν θα νόμιζε πως εκείνα στην πραγματικότητα είναι πιο ευκρινή από αυτά που του δείχνουν;

Έτσι, είπε.

Και αν, είπα εγώ, τον τραβούσε κανείς με τη βία από εκεί, μέσα από ένα δρόμο κακοτράχαλο κι ανηφορικό, και δεν τον άφηνε, πριν τον τραβήξει έξω στο φως του ήλιου, δεν θα υπέφερε τάχα και δεν θα αγανακτούσε όταν τον έπαιρναν, κι αφού θα έφτανε στο φως, δεν θα πλημμύριζαν τα μάτια του από τη λάμψη και δεν θα του ήταν αδύνατο να δει ακόμα κι ένα απ' αυτά που τώρα ονομάζονται αληθινά;

Όχι βέβαια, δεν θα μπορούσε έτσι ξαφνικά, είπε.

Έχω την εντύπωση πως θα χρειαζόταν να συνηθίσει, αν σκοπεύει να δει τα πράγματα που είναι πάνω. Και στην αρχή θα μπορούσε πολύ εύκολα να διακρίνει καλά τις σκιές, και μετά απ' αυτό, πάνω στην επιφάνεια του νερού τα είδωλα των ανθρώπων και των άλλων πραγμάτων, και κατόπιν αυτά τα ίδια. Και μετά από αυτά, τ' αντικείμενα που είναι στον ουρανό και τον ίδιο τον ουρανό θα μπορούσε να δει ευκολότερα τη νύχτα, βλέποντας το φως των άστρων και της σελήνης, παρά στη διάρκεια της μέρας, τον ήλιο και το ηλιόφως.

Πως όχι;

Τελευταίο θα μπορούσε νομίζω να δει τον ήλιο, όχι στην επιφάνεια του νερού ούτε σε κάποια διαφορετική θέση τα είδωλά του, αλλά θα μπορούσε να δει καλά τον ήλιο καθαυτό στο δικό του τόπο και να παρατηρήσει προσεκτικά τι είδους είναι.

Κατ' ανάγκη, είπε.

Και μετά θα συλλογιζόταν τότε για κείνον, πως αυτός είναι που ρυθμίζει τις εποχές και τους χρόνους και που κανονίζει τα πάντα στον ορατό κόσμο, καθώς και ο αίτιος, κατά κάποιο τρόπο, όλων εκείνων που έβλεπαν αυτοί.

Είναι φανερό, είπε, πως αυτά θα συμπεράνει ύστερα από τα προηγούμενα.

Τι λες λοιπόν; Όταν αναλογίζεται την πρώτη του κατοικία και την εκεί σοφία που είχε αυτός και οι τότε συνδεσμώτες του, δεν νομίζεις πως θα καλοτυχίζει τον εαυτό του για τούτη την αλλαγή και θα οικτίρει τους άλλους;

Και πολύ μάλιστα.

Κι αν υπήρχαν μεταξύ τους τότε κάποιες τιμές και έπαινοι και βραβεία γι' αυτόν που θα μπορούσε να διακρίνει πιο καθαρά αυτά που περνούσαν μπροστά από τα μάτια του και γι' αυτόν που θα μπορούσε να θυμηθεί περισσότερο ποια συνήθως περνούσαν πρώτα, ποια μετά και ποια ταυτόχρονα, και έτσι θα μπορεί να προβλέπει τι θα έρθει στο μέλλον, νομίζεις πως αυτός θα κατεχόταν από σφοδρή επιθυμία και θα ζήλευε τους τιμημένους από κείνους και τους μεταξύ εκείνων κυρίαρχους ή θα είχε πάθει αυτό που λέει ο Όμηρος, και πολύ θα επιθυμούσε "να ήταν ζωντανός στη γη κι ας δούλευε για άλλον, που είναι ο φτωχότερος" και θα προτιμούσε να έχει πάθει τα πάντα, παρά να νομίζει εκείνα που νόμιζε και να ζει έτσι εκεί;

Έτσι νομίζω τουλάχιστον, είπε, πως θα προτιμούσε να πάθει οτιδήποτε παρά να ζει έτσι.

Και τώρα βάλε στο μυαλό σου το εξής, είπα εγώ. Αν κατέβει αυτός πάλι και καθίσει στον ίδιο θρόνο, δεν θα ξαναγεμίσουν τάχα τα μάτια του σκοτάδι, αφού ήρθε ξαφνικά από τον ήλιο;

Και πολύ μάλιστα, είπε.

Αν χρειαζόταν ν' ανταγωνιστεί αυτός με κείνους τους παντοτινούς δεσμώτες, λέγοντας την άποψή του σχετικά με τις σκιές, καθόσον χρόνο η όρασή του είναι αμβλεία, πριν προσαρμοστούν τα μάτια του, και για να συνηθίσουν δεν θα χρειαζόταν και τόσο μικρός χρόνος, άραγε δεν θα προκαλούσε περιπαιχτικά γέλια και δεν θα έλεγαν γι' αυτόν πως με το ν' ανεβεί επάνω, γύρισε με καταστραμμένα τα μάτια του και πως δεν αξίζει ούτε να προσπαθήσουν καν να πάνε επάνω; Και αυτόν που θα επιχειρήσει να τους λύσει και να τους ανεβάσει, αν τους δινόταν κάπως η ευκαιρία να τον πιάσουν και να τον σκοτώσουν, δεν θα τον σκότωναν;

Αναμφίβολα, είπε.

Αυτή την εικόνα λοιπόν, φίλε μου Γλαύκωνα, είπα εγώ, πρέπει να την προσαρμόσεις σε όλα όσα είπαμε πρωτύτερα και να παρομοιάσεις τον ορατό κόσμο με την κατοικία του δεσμωτηρίου, και τη φωτιά που αντιφέγγιζε μέσα σ' αυτή με τη δύναμη του ηλιακού φωτός. Αν όμως παρομοιάσεις την ανάβαση και τη θέα των αντικειμένων, που βρίσκονται στον επάνω κόσμο, με την άνοδο της ψυχής στον νοητό κόσμο, δεν θα σφάλεις ως προς τη δική μου άποψη, αφού επιθυμείς να την ακούσεις. Κι ο θεός τουλάχιστον ξέρει αν τυχαίνει να είναι αληθινή. Εμένα λοιπόν έτσι μου φαίνεται. Πως στην περιοχή του γνωστού η ιδέα του αγαθού είναι τελευταία και μετά βίας διακρίνεται, όταν όμως τη διακρίνει κανείς δεν μπορεί να μην συλλογιστεί πως αυτή είναι η αιτία για όλα γενικά τα σωστά και καλά πράγματα, γεννώντας μέσα στον ορατό κόσμο το φως και τον κύριο του φωτός, και γιατί μέσα στον νοητό κόσμο αυτή είναι που διευθύνει και παρέχει την αλήθεια και τον νου και πως πρέπει να την ατενίσει οπωσδήποτε αυτός που εννοεί να ενεργήσει φρόνιμα και στην ιδιωτική και στη δημόσια ζωή.